Haven’t read Part 1? Read it here before Part 2.

There is an interesting backstory to the events involving Harry Stackpole. That is because he was the son of P.A. Stackpole, a local dentist/physician for many years, and one of Dover’s leading citizens. Paul Augustine Stackpole attended Wolfeboro Academy for two years, then Andover. He studied medicine with local doctors Joseph Smith and Noah Martin (the latter at one point was elected New Hampshire’s Governor), then attended Boylston Medical School in Boston, sat in on lectures at Harvard, and graduated from Dartmouth in 1843. Early on, he lived at 8 Orchard St., next door to his office in the so-called Marston Building at the corner of Orchard Street and Central Avenue. (The building burned on Jan. 6, 1862, forcing Stackpole and other tenants out into a below-freezing day.)

Stackpole was an early advocate of advertising: “Dentistry in all its departments… done in the best possible manner” and, in 1864, “After long experimenting, and at great expense, we can assure the public that we can manufacture a pure article nitrous oxide gas as an anesthetic for the extracting of teeth without pain”.

But in addition to his professional pursuits, he was an active and valued community member. President of the County Medical Society in 1856-57, and later President of the New Hampshire Medical Society. A delegate to the national Democratic convention in 1864 (it was held in Chicago, and the nominee was former Union General George McClelland). He served on the Dover School Board, was an active Mason and Odd Fellow, and was asked to be one of the featured speakers at the opening of the Portsmouth & Dover Railroad. He was one of the founders and, for a time, served as editor of a short-lived local newspaper, the State Press. And last, but not least, he was a soloist with the Dover Choral Society.

Stackpole was married, and there were three children. Unfortunately, his wife died eight years into the marriage, and he never remarried. It appears that after retirement, he was living in Harry Stackpole’s home on Second Street. On March 28, 1900 (one reports says the 30th) P.A. slipped on a carpet at the head of a flight of stairs, fell, and died instantly. He was found by his son. Following his funeral, it was reported that the “floral tribute was beautiful and contributed with a lavish hand, for the Doctor loved flowers, and his friends knew it.”

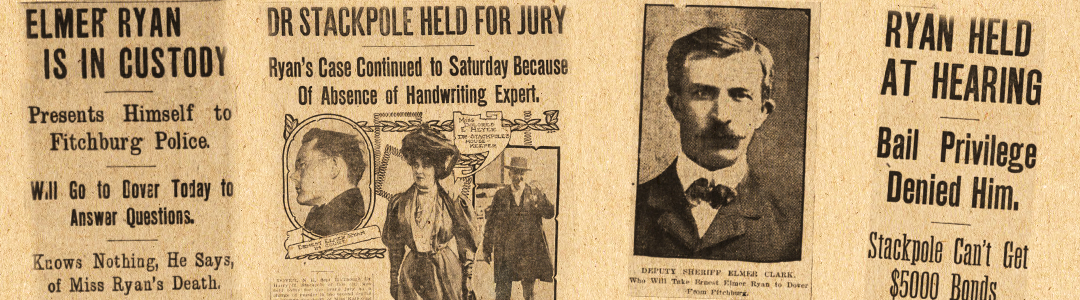

Harry appears not to have had the same level of community involvement as his father. His home and office were on Second Street, and there is no mention of a wife or children in any newspaper reports. The major focus on the 30th was on the person of Elmer Ryan, who had been located in Fitchburg, Mass. It may have been that he had heard of the matter in Dover, because he showed up at the central police station in Fitchburg and, as reported by the press, “practically gave himself up”.

He was identified as a former employee of the National Biscuit Company who, with a friend, was in the process of buying a restaurant in Lowell. The wife of the present owner asked him if he knew a Katherine Ryan. He did. Did he know she was dead? He did not. She advised that he should go to the police. He did. Strafford County Deputy Sheriff Elmer Clark appeared and asked that Ryan be placed under arrest, but Ryan offered to return to Dover voluntarily. Under questioning, he admitted knowing Katherine Ryan, acknowledged that he may have “called on her” on occasion, but denied that he paid her attention “steadily”. He expressed surprise at learning of her death and stated he was not aware that she had been in Dover at any time. He was taken into custody and brought to Dover, where he spent the night in jail. Solicitor Hall said he could not address any of the specifics as to Elmer’s Ryan’s role in the death, but felt the arrest strengthened the State’s case against Dr. Stackpole.

There was something of a sideshow as Ryan was removed from Hall’s office and moved to the jail, which was then located within Dover’s present-day waterfront development area. Turned out to be a large crowd lining the route on Washington Street to observe the transfer. A woman by the name of Mary Killoren, a resident of Rochester, had been in town partaking of some alcoholic beverages, and she took offense to some comments being made by a group of young boys gathered along the route. “She sailed into them, right and left and landed one or two of them quite a hard wallop in the head which caused the remainder of the gang to take leg bail.” A Dover police officer, standing nearby, observed the event, and Mary was arrested. She appeared in the District Court the following morning, was found guilty of public intoxication, and fined. It was duly noted that this was not Miss Killoren’s first run-in with local authorities.

Ryan was arraigned in District Court on the 31st on a formal charge of having been an accessory before the fact of Katherine Ryan’s death. Long before the time set for the hearing, the streets around City Hall — the location of the court — were crowded with spectators, and the courtroom was packed to capacity. It was reported that Ryan “looked at the crowd over with interest.” When County Solicitor Hall notified the court that counsel would represent Ryan, but that person was unavailable until later in the day, the hearing was postponed until the afternoon. At 4 p.m., with an attorney present, one J.H. Bent, “who is said to be a well-known lawyer in Lowell,” Ryan waived a reading of the complaint and entered a plea of not guilty.

One of the people present for the hearing was Stackpole’s housekeeper, Emily Heyer, accompanied by her sister Maud. She had been summoned to appear as a potential witness in the event of an evidentiary hearing. According to Foster’s, Emily “…did not appear to be suffering from the great mental strain that she had been reported to have been suffering the past few days.” Just to be on the safe side, however, the authorities had been maintaining surveillance on Stackpole’s home, “to keep a watch” on Heyer’s movements should she attempt to leave the area.

One interesting report refers to a number of letters, apparently written but not mailed, from the deceased to several people connected to this story: her friend, Loretta Rabbit, her aunt, Mrs. Graffam, and several other individuals in Lowell. The exact contents were not divulged, but some of the statements were disturbing enough that they led Solicitor Hall to revoke his decision to allow Stackpole to remain at home under surveillance, instead having him actually jailed pending his court appearance. While there, “Dr. Stackpole…is reported as being in good health and in feeling in as good spirits as possible for a man who is placed in the position that he is.”

And in a rather remarkable coincidence, amid all the various reports of the Stackpole affair, there was a front-page article reporting that on the 30th the 10th-annual Reunion of the Stackpole Family of America had been held in Rollinsford, attended by about 60 descendants of James Stackpole, who had settled in that community in 1680. The gathering had been called to order by the President of the Society, Mrs. Annie W. Baer.

Given all the bad publicity coming out of Dover regarding Doctor Harry, the timing of the reunion could not have been worse.

(To be continued)

Read Part 3 of “Death at the Doctor’s House: The Stackpole Affair” here.

Visit the Crimes Along the Cochecho for all stories released so far.

Anthony McManus is a Dover, New Hampshire historian whose column “Crimes Along the Cochecho” explores the darker chapters of local history. A Dover native and Boston College Law School graduate, McManus served as City Attorney for Dover (1967-1973) and held various public offices before practicing law until 2001. His extensive historical work includes the “Historically Speaking” column in Foster’s Daily Democrat and his 2023 book “Dover: Stories of Our Past,” released for the city’s 400th anniversary. Through research, writing, and public presentations, McManus continues to illuminate both significant events and lesser-known stories that enrich understanding of Dover’s colorful past.